Even a single transposed digit on a pharmaceutical label can put patients at risk and lead to costly recalls. The companies that stay inspection-ready are the ones that not only know the requirements but also understand where errors most often occur.

Introduction to Pharmaceutical Labeling

Pharmaceutical labeling includes every element that appears on drug packaging. This covers not only the words but also graphical components such as logos, color bands, barcodes, Braille, and regulatory symbols across everything from vial text and prescribing information to promotional materials and package inserts. The FDA's definition under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act casts a wide net - if it accompanies your drug, it's labeling. But different markets have different regulators. In the U.S., it’s managed by the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Europe assigns the task to the EMA, while Japan relies on the PMDA. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has narrowed the gaps through harmonization, but true content harmonization remains a work in progress. Regional differences persist, not just in language and translation, but in data requirements, content order, and local risk/benefit priorities. This means that a label that clears FDA review may still need revision before European regulators accept it.

Pharmaceutical labeling also covers over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, which have their own standardized “Drug Facts” label format. Unlike prescription labeling, which is written for healthcare providers, OTC labeling must be self-explanatory for consumers. Typography rules for OTC labeling are unusually strict. The FDA’s Drug Facts regulation requires text to be at least 6-point type, with bolded headings and a layout that remains legible at arm’s length. Within that format, FDA also specifies the elements that must appear, in this order:

- Active ingredient(s): name and strength per dosage unit

- Purpose: the drug category or intended effect

- Uses: approved indications

- Warnings: including “Do not use” statements, precautions for pregnancy/breastfeeding, and when to consult a physician

- Directions: dosage instructions for safe use

- Inactive ingredients: listed for allergy awareness

Unclear dosing instructions and poorly placed contraindications leave consumers without the full information they need to use products safely. Regulatory scrutiny keeps intensifying because the risks of misunderstanding are that high.

FDA Labeling Resources for Prescription Drugs

The FDA runs several databases for accessing official labeling information. Drugs@FDA is the most comprehensive, holding approval information, prescribing details, and labeling history for thousands of approved drugs. Need to see how a label evolved? This is where you search.

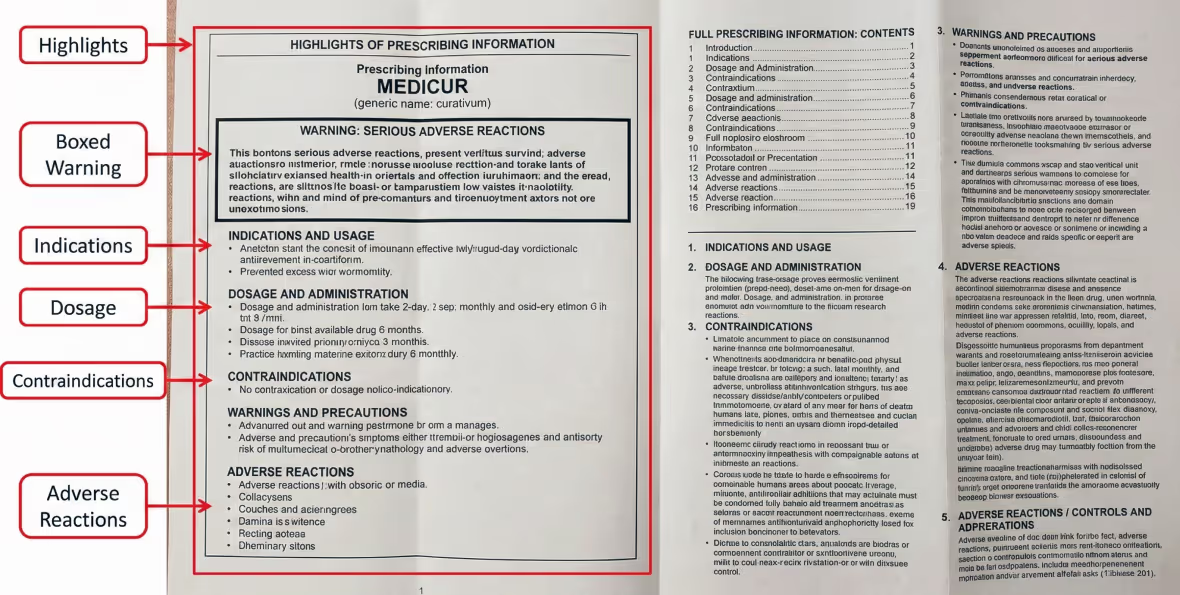

DailyMed, operated by the National Library of Medicine with the FDA, publishes standard product labeling in structured format. Healthcare providers use it when checking prescribing information at point of care. When navigating either portal, start with the "Highlights" section, which summarizes critical prescribing information before the detailed sections on clinical pharmacology and storage requirements.

During regulatory inspections, auditors compare production labels against official submissions. The FDA-approved version represents what the agency reviewed and cleared, while current labeling reflects the most recent updates. Quality teams should reference the FDA-approved version as the compliance benchmark, not whatever's on DailyMed right now. That distinction matters when inspectors show up with your submission documents in hand.

Prescribing Information Components

Professional prescribing information follows the Physician Labeling Rule format, which divides content into two main sections: Highlights and Full Prescribing Information.

Labeling for pediatric patients requires special considerations beyond what appears in Section 8 of prescribing information. Under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA) and the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA), manufacturers must submit pediatric-specific clinical data rather than relying solely on adult studies. In practice, pediatric labeling combines weight-based dosing tables with clear instructions on age-appropriate formulations. It also calls out safety warnings where risks exceed potential benefits. These details help prevent inappropriate off-label use, a leading cause of dosing errors in children, giving healthcare providers information they can apply directly in real-world care.

For clinical trial data, prescribing information must go beyond headline results. For labeling to be meaningful, it needs to present absolute risk reduction in a way that reflects the characteristics of the study population and the length of follow-up. Without this context, providers can't assess whether trial results apply to their patients. In hospital settings, clinical decision support systems pull this data to flag potential problems before medications reach patients.

Patient Labeling Requirements

Patient labeling takes medical information and makes it accessible to people without clinical training. The FDA requires specific formats based on drug class and risk profile: Medication Guides, Patient Package Inserts, and Instructions for Use. Medication Guides are mandatory when information about preventing serious adverse effects is critical for safe use. These one-page documents explain risks in plain language, often using question-and-answer format. The FDA pre-approves exact wording, meaning manufacturers can't modify content without agency clearance.

Clear communication in labeling goes beyond simple vocabulary choices. The FDA expects plain language - active voice over passive constructions, short sentences over complex ones, everyday terminology over medical jargon. When technical terms are unavoidable, plain-language definitions must follow immediately. Research shows patients are more likely to follow dosing instructions and recognize warning signs when labeling speaks their language.

Layout plays an equally important role in patient understanding. Pages that feel open and structured are easier to navigate, and strong headings guide readers to the details they need. For older adults, larger type often makes the difference between clear instructions and missed doses. To reinforce this, the FDA mandates minimum font sizes and high contrast between text and background, recognizing that labeling only works if patients can actually read it. Many teams now use automated font-size verification tools to ensure compliance before packaging reaches production.

Carton and Container Labeling Standards

The first layer of packaging is the container that touches the drug itself, and it must carry the details needed for safe use. A second layer, for example cartons or shippers, supports the supply chain by showing additional information.

The FDA specifies the content required for both:

Primary Container:

- Drug name

- Strength

- Route of administration

- Lot number

- Expiration date

Secondary Packaging:

- Full product name

- Active ingredients

- Dosage form

- Net quantity

- Storage conditions

- Manufacturer details

- National Drug Code (NDC)

Space constraints on small containers create a practical challenge. When the container is too small to hold every required element, the FDA permits certain details to appear only on the carton, as long as the two remain together through distribution. The National Drug Code (NDC) is critical here, serving as a unique identifier that ties the package back to FDA registration. This reduces the risk of medication mix-ups in pharmacies and clinical settings.

Safety information is not presented uniformly across all products. Storage conditions, such as refrigeration or protection from light, are highlighted prominently when product-specific guidance requires it. Controlled substances come with their own rules: the DEA requires the schedule symbol (I–V) to appear prominently on the label in type larger than the drug name. If the symbol remains visible through the packaging, outer cartons do not need to carry it separately. Barcoding addresses another layer of risk by enabling traceability across the supply chain and reinforcing both FDA and DEA requirements.

Barcode labeling requirements have evolved alongside electronic medication systems. Under 21 CFR 201.25, the FDA requires that many prescription drug labels include a barcode that at minimum encodes the NDC. In real-world practice, pharmacy and clinical systems scan that barcode during dispensing or administration to confirm the product and detect mismatches that manual transcription might miss.

[Visual: Annotated pharmaceutical carton showing NDC placement, barcode specifications, warning statement positioning, lot/expiration formatting, storage condition display]

Generic Drug Labeling Considerations

Generic drug labeling follows a sameness standard with specific exceptions. The FDA requires generic drugs to match the reference listed drug on essentials: indications, dosage, administration route, strength, and active ingredient.

Clinical content in a generic label must be identical to the reference listed drug (RLD). That includes warnings and precautions, as well as the language covering adverse reactions and drug interactions. If the brand carries a boxed warning, such as one for cardiovascular risk, the generic repeats the warning in the same placement and format. The areas where generics have leeway are business-related. A manufacturer can use its own name and contact information, update the “How Supplied” section to match its packaging, and leave out patent or exclusivity statements that apply only to the branded product.

FDA continues to emphasize the need for generics to keep labeling aligned with current safety information. Under section 505(o)(4), the agency can require updates when new risks are identified, ensuring that both the reference listed drug and approved generics carry the same warnings. While FDA oversight is tightening, the mechanism for rapid safety alignment has been subject to reform, and timing of updates can vary in practice. Some alignment still lags despite regulatory emphasis.

Biological Products Labeling Requirements

Biological products differ from traditional drugs in important ways. Traditional drugs are synthesized through predictable chemical processes. Biologics are produced in living systems (bacterial cells, yeast, mammalian cell cultures), where product characteristics can vary between production batches in ways that affect safety and efficacy.

A biosimilar is a biological product that is highly similar to an already approved reference product, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, or potency. Biosimilar labeling must clearly identify the product as biosimilar and include the reference product name. The Purple Book lists all licensed biological products and approved biosimilars for verifying nomenclature and interchangeability status. Products designated as interchangeable can be substituted by pharmacists like generics, while non-interchangeable biosimilars need prescriber approval first.

Immunogenicity is among the key safety concerns for biologic products. Patients may develop anti-drug antibodies, potentially reducing therapeutic effect or triggering adverse reactions. Labeling should report immunogenicity findings from clinical studies, and where available include identified risk factors and suggested monitoring for clinicians. Because biologics sometimes behave differently in broader clinical use than in controlled trials, the FDA often requires postmarketing safety studies. Requirements vary depending on the specific product and epidemiologic risk. Health Canada's 2025 guidance revisions are shifting toward less prescriptive data requirements with certain study waivers, though consultation on final guidance is ongoing. When labeling refers to postmarketing commitments, it signals to providers that safety information is evolving, not static.

International Labeling Harmonization

Global labeling isn’t uniform. Companies selling products across borders face overlapping rules in some regions and conflicting ones in others. ICH has narrowed many of the gaps through guidelines adopted by major authorities, but important differences remain.

Among the most influential ICH efforts is the M4 guideline, which introduced a common technical document format. Rather than building a new package for each regulator, companies can use the ICH format to organize early research and clinical data consistently. The same submission also carries the quality information regulators expect, allowing it to be sent to multiple agencies without rework. It’s the closest thing the industry has to a universal standard.

Regional expectations still shape how labels look in practice. The EMA, for instance, requires patient information leaflets in all EU languages, each one reviewed and approved as part of the authorization process. Translations can’t simply mirror the English version, they have to reflect local context and health literacy while staying medically precise. Japan’s PMDA takes another path, with insert requirements tied closely to local clinical practice and regulatory norms.

Moving drugs across borders adds complexity of its own. Labels must match the requirements of the destination market even when the formulation is unchanged. Certain authorities add local requirements such as establishment license numbers or import registration identifiers. To comply, companies often have to produce separate label designs even when the underlying product is identical.

Promotional Labeling Regulations

The FDA treats any material a manufacturer distributes about its products as labeling, whether it’s a journal advertisement, a conference booth handout, or a sales presentation. All of it must stay consistent with the FDA-approved label. That requirement is enforced through the principle of fair balance: risks and benefits have to be presented with equal weight. An ad that highlights reduced disease progression must also give side effects, contraindications, and usage limitations the same visibility. Burying risks in fine print or glossing over them in broadcast spots is one of the quickest ways to draw an FDA warning letter.

The FDA's Office of Prescription Drug Promotion monitors both formal advertising and sales activity. Overstating efficacy, minimizing risks, pushing off-label uses, or making misleading comparisons with competitors all fall under its scope. Because FDA defines labeling broadly, not only do journal ads and booth materials count, but so do the verbal statements sales reps make in physician offices. Minor violations may result in untitled letters, while serious cases trigger warning letters and escalating enforcement.

Digital Labeling and Electronic Resources

Electronic prescribing information has become the primary distribution channel for drug labeling. The FDA allows companies to provide prescribing information via email or other electronic means to healthcare providers who consent to receive it this way, reducing paper distribution while speeding up how quickly labeling updates reach prescribers.

Structured product labeling (SPL) runs the technical infrastructure. SPL uses XML formatting to encode prescribing information in machine-readable format. When pharmacies check for drug interactions or electronic health records flag contraindications, they're pulling data from SPL files submitted to the FDA. This automation surfaces critical information at point of care without requiring manual reference checks.

QR codes bridge the gap between limited packaging space and the full range of digital content patients and providers may need. Scanning a code can pull up prescribing information, medication guides, administration videos, or updated safety notices. The FDA does not require QR codes yet, but the direction of travel is clear. The EU has already taken the lead with electronic labeling initiatives, and U.S. discussions around replacing linear barcodes are picking up speed. QR-enabled packaging is fast becoming the industry’s default for delivering updated safety, prescribing, and traceability information. It’s a question of when, not if, those standards take hold. . New digital tools are emerging even as regulatory frameworks take time to catch up:

- Augmented reality applications are in exploratory trial phases, with some regulatory sandboxes testing whether patients could point a smartphone at a medication bottle to see visualizations of how the drug works or receive personalized dosing reminders.

- Blockchain systems are being tested for tamper-proof records of labeling changes and for stronger supply chain verification

- AI-powered translation tools could one day generate real-time labeling in the patient’s preferred language.

Before new technologies can move beyond pilot use, regulators must first define how they’ll be validated, then set rules for content control and accessibility.

Clinical Significance of Proper Labeling

In 2016, hyoscyamine tablets were recalled when batches contained tablets of wildly inconsistent strength - some superpotent, others subpotent. Patients taking what they thought were standard doses were actually getting unpredictable amounts of medication. Years earlier, Pfizer recalled approximately 1 million packs of birth control pills when incorrect packaging put tablets in the wrong order, compromising contraceptive effectiveness for patients who had no reason to suspect anything was wrong.

Labeling failures like these make headlines, but proper labeling quietly supports clinical decisions every day. When contraindications are easy to find, emergency physicians can act quickly to avoid dangerous drug interactions. Nurses rely on dosing tables for a different reason, using them to confirm that the prescribed dose falls within approved ranges before the drug is given. Prominent warnings about drug interactions surface in pharmacy systems, triggering reviews that catch dangerous combinations before medications reach patients.

Some labels technically comply but still fail in practice. Minimum font sizes, for instance, often become hard to read under dim lighting in hospital corridors. Regulatory wording may be accurate yet phrased in a way that clinicians don’t immediately recognize during emergencies. Barcodes present a different problem: they can pass inspection at first but degrade in printing, which disrupts automated verification at the point of care.

Healthcare Professional Responsibilities

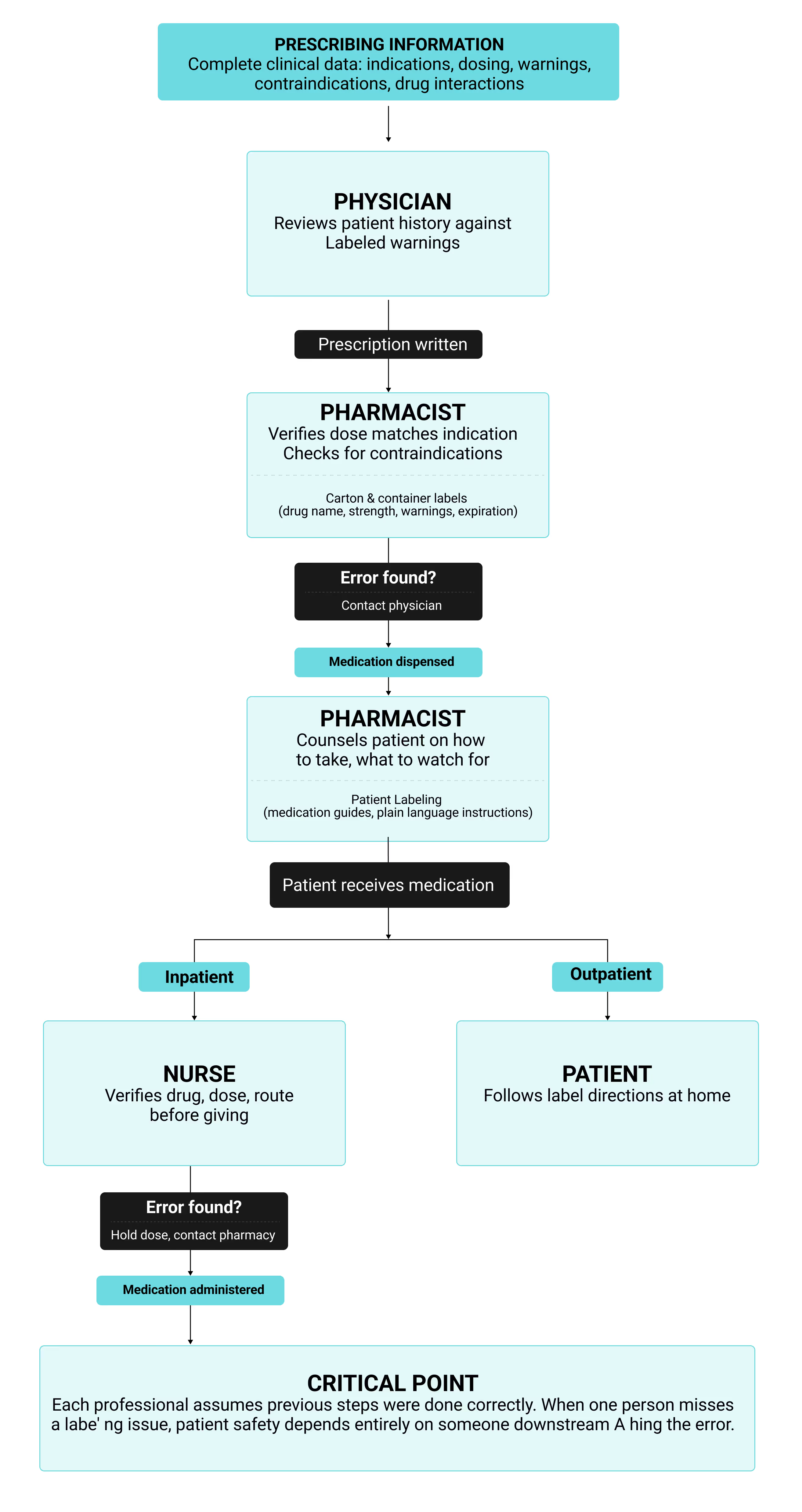

Prescribing information in a pharmacy database is useless unless it guides decisions at every step of care. That means physicians check contraindications before writing an order, pharmacists confirm the dose against labeled indications, and nurses read the vial before preparing the medication. Understanding how labeling moves through the medication use process reveals where vulnerabilities exist. Each professional relies on different labeling formats at different decision points, creating a chain of verification steps that only works when every link holds. The flowchart below maps these touchpoints and shows how errors that slip past one checkpoint become the next person's problem to catch:

This interconnected system means pharmaceutical manufacturers can’t view labeling as a simple regulatory checkbox. When prescribing information is poorly organized, physicians working under time pressure may overlook it entirely. Pharmacists run into another problem when terminology on cartons isn’t consistent, which slows their review and distracts from catching real errors. Critical warnings buried in dense patient labeling paragraphs go unread by the people who need them most. Each labeling failure cascades through the system, multiplying the chance that an error reaches a patient before someone catches it.

Labeling Compliance and Updates

When new safety information emerges, the FDA can require labeling updates under section 505(o)(4) of the FD&C Act. The type of submission depends on the change. Editorial fixes that don’t affect safety or effectiveness can be documented in annual reports. Changes to indications, dosage, contraindications, or warnings require prior FDA approval before they take effect. For safety-driven updates, the process moves fast:

- FDA notification letter outlines the new safety concern.

- 30-day response window for the company to submit revised labeling or explain why a change isn’t needed.

- FDA review and approval follows for proposals that meet the requirement.

- Agency order may be issued within 15 days after discussions end if the company and FDA cannot reach agreement.

Identical drugs sometimes carry different warnings in different markets. That happens when the EMA approves a safety update months ahead of the FDA, creating gaps in version control across jurisdictions. Tracking which version applies in each market and keeping specifications accurate at production sites are only part of the challenge. Companies also need safeguards to prevent inventory from being mixed up during distribution, especially when multiple regions are involved.

When health-care professionals see labeling problems, they can report them to FDA through MedWatch. Manufacturers must investigate and determine if corrections are needed. The system only works when professionals actually report what they see instead of assuming someone else will.

Non-compliant labeling sets off a chain of FDA enforcement actions. Inspectors usually note minor violations on an FDA-483, which requires a written response and a corrective plan. More serious issues bring warning letters, and those letters become public record. This often draws scrutiny from both regulators and the market. If problems continue, the FDA can escalate to a consent decree or even stop manufacturing. Labeling violations also create liability when patients suffer harm. Recalls and supply interruptions add direct financial loss, while reputational damage erodes market position long after the compliance issue has been corrected.

Common Labeling Issues and Solutions

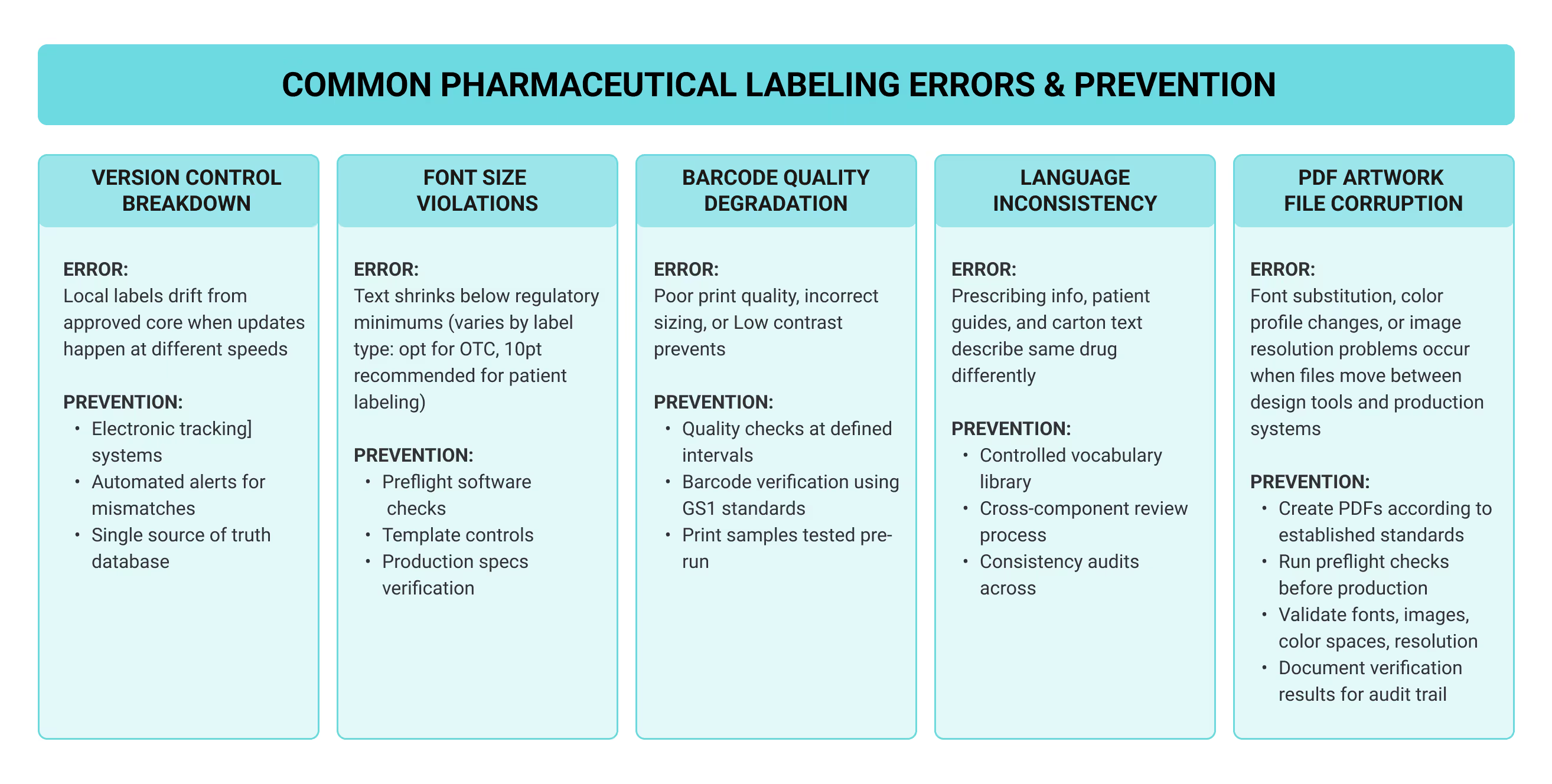

Most labeling compliance problems come from version control breaking down across global markets. Companies marketing products in multiple regions watch local labels drift from core company data sheets when updates happen at different speeds. Translation makes it worse, requiring accurate adaptation to each language while maintaining consistency with approved source material demands coordination that manual tracking can't handle at scale.

Technical errors get through manual review all the time. Font sizes shrink below requirements under space pressure. Barcode quality degrades during printing. When label artwork moves between design tools and production systems, pdf files can have font substitutions or color profile shifts happen quietly. Preflight software catches these problems before production by checking fonts, images, color spaces, and resolution automatically.

Compliance teams have moved past basic checks by embedding automated workflows into their processes with preflight profiles. These workflows surface issues in real time, letting teams correct errors as they appear, and the preflight results document every fix before the files advances to production. Teams use tools like Adobe Acrobat to verify that labeling artwork meets FDA and ISO PDF standards before print, ensuring consistent appearance and accuracy across every approved version. When this process is standardized, companies cut down on re-printing and costly corrections while ensuring important details remain accurate through every version, keeping documentation consistently audit-ready.

Modern production tools also support full pdf workflows, from file creation in InDesign to archiving in centralized systems. For customers working with contract manufacturers, sharing these files ensures the final output reaching the press matches approved specifications exactly. The result is output that remains consistent across users and product categories worldwide. For global operations, storing and sharing files through platforms like Google Drive ensures version control and lets documents be displayed automatically in the correct format.

In pharmaceutical labeling workflows, preflight software refers to automated file-checking tools that flag issues like fonts, images, color spaces, or resolution before production. These checks ensure labeling accuracy and compliance from approval through final print.When automation and reporting tools are integrated with production systems, quality teams no longer face trade-offs. They can resolve errors before print while keeping every file aligned with FDA requirements and industry pdf standards. There is no perfect solution for labeling compliance, but integrated preflight checks with automation prevent most errors before production.

Common questions about labeling compliance:

- How do I know if a change needs prior approval? If a change affects indications, dosage, warnings, or contraindications, the FDA must review and approve it before implementation. Minor editorial edits and corrections can usually wait and be reported in the annual update. Always record which version is active and keep documentation to show how updates were handled.

- What do I do when I find labeling errors after approval? Errors discovered after approval must be reported through FDA’s MedWatch system. Once reported, the quality team investigates the issue, identifying the root cause and applying a fix within the established workflow. Documenting how the correction was applied keeps the record inspection-ready.

- Why must the National Drug Code (NDC) appear on labels? The National Drug Code (NDC) is the product’s unique identifier, linking the product back to FDA registration and preventing mix-ups during dispensing. On the printing line, it provides the detail needed to confirm that every box and package matches the correct drug version.

- Who reviews and approves pharmaceutical labels? In the U.S., the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) is responsible for label review and approval. For controlled substances, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) enforces additional placement and warning requirements. Guidance is available directly through FDA’s labeling resources on the agency’s official web portals.

- What are the penalties for non-compliance? Penalties can include FDA-483 observations, warning letters, recalls, or suspension of manufacturing. These actions also carry significant financial costs, including recall execution, product loss, halted production, and remediation expenses. The larger cost often comes afterward, with companies facing reputational harm and potential liability. They also risk losing market access. Meeting labeling requirements avoids these consequences and protects patients.

- What tools help ensure labeling compliance? Teams often rely on preflight software together with tools like Adobe Acrobat or InDesign plug-ins to check pdf files before printing. These tools confirm fonts, images, ICC profiles, and color spaces are correct. They also generate a preflight report with details on each correction and store every version so audits can move quickly and records remain clear.

- Can you give an example of common errors that software detects? Common issues include transparency conflicts, missing or low-resolution logos, and font substitutions in pdf workflows. Catching these problems before files go to print reduces re-printing and ensures consistent quality across every category of product.

- What documentation should companies maintain? Companies should keep an archive that includes approved labels along with submission packages and regulatory correspondence. Documents must be ready for inspection at any point. Many organizations also provide internal courses so staff follow consistent documentation practices.

- Who is responsible for reviewing and approving pharmaceutical labels internally? While the FDA or other regulators grant final approval, the internal review process is handled first by the company’s own teams. Regulatory affairs and quality assurance staff usually lead, and they draw on additional expertise when medical accuracy, legal risk, or packaging design need closer scrutiny. Each step is documented so that by the time a label is submitted to the FDA, the company can show that every internal checkpoint has been completed.

Key resources:

- FDA's "Safety Considerations for Container Labels and Carton Labeling Design to Minimize Medication Errors" (May 2022)

- "Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products – Implementing the PLR Content and Format Requirements"

- FDA Division of Medication Error Prevention and Analysis (for specific compliance questions)

Future Directions in Pharmaceutical Labeling

Most clinical settings no longer rely on paper prescribing information. Instead, electronic distribution supplies structured product labeling data that pharmacy systems use to generate drug interaction alerts and support clinical decisions. QR codes link physical packaging to digital content that won't fit on containers. These aren't emerging technologies, they’re the reality of how labeling works now.

Global harmonization through ICH has aligned core documentation requirements, but regional differences remain entrenched. While efforts like Canada’s XML PM format moving closer to FDA’s SPL show progress, differences in patient leaflet requirements and biologics guidance remain significant across jurisdictions. The EMA demands patient information leaflets in all official EU languages with market-specific adaptations. Japan's PMDA maintains distinct package insert requirements. Companies managing products across markets still handle multiple label versions for identical drugs, though better data systems have reduced the errors manual tracking created.

Patient accessibility is an area of constant change. Regulators are moving beyond general statements about plain language and now define more clearly what qualifies as patient-friendly communication, rather than what simply satisfies a compliance checkbox. Digital formats open the door to personalization. A patient could adjust font size for readability, switch to their preferred language, or choose an audio version. These tools are not yet formally recognized for regulatory purposes. Both US and Canadian authorities have legislative and regulatory reviews underway, meaning adaptive labeling remains an evolving standard rather than established practice.

At the same time, regulators are drawing more heavily on real-world evidence. Data from electronic health records and patient registries now plays a growing role in shaping labeling requirements and approval decisions. As agencies fold real-world data into safety monitoring, label updates may move on a faster timetable than the traditional annual cycle. The real test will be how quickly manufacturers adapt their systems, since frequent changes increase the risk of version control failures and labeling errors.

GlobalVision's Verify is built for the inspection challenges pharmaceutical teams face when compliance can't wait for human error to surface. See how Verify works.